Mancetter - St Peter

Mancetter lies immediately south east of Atherstone, adjacent to the A5, or by it's ancient name Watling Street, and fittingly itself was a Roman settlement known as Manduessedum, a posting station straddling the road. Nothing of the Roman period remains today beyond some earthworks, but the village does possess a fine medieval church surrounded by picturesque cottages, and despite being in an area notorious for locked churches is worth a visit.

The church is of mainly 13th -14th century date and has a fairly squat west tower (it's red sandstone upper storey is Perpendicular) which does not dominate the area like it's immediate neighbour at Witherley on the opposite side of the A5 over the Leicestershire border (a nearby church with a lofty steeple that I always used to confuse with this one years ago!). Nonetheless it is a fairly large building with a nave flanked by spacious aisles and a long chancel, lit by a fine set of three-light windows on each side. The tower is pushed against the western perimeter of the churchyard and had no room for a walkway around it, this it is pierced by an archway on it's north and south sides, allowing space for processional routes. Today these arches are glazed in, and the main points of entry are via the Georgian south porch or the modern parish rooms extension abutting the north west corner.

The church is of mainly 13th -14th century date and has a fairly squat west tower (it's red sandstone upper storey is Perpendicular) which does not dominate the area like it's immediate neighbour at Witherley on the opposite side of the A5 over the Leicestershire border (a nearby church with a lofty steeple that I always used to confuse with this one years ago!). Nonetheless it is a fairly large building with a nave flanked by spacious aisles and a long chancel, lit by a fine set of three-light windows on each side. The tower is pushed against the western perimeter of the churchyard and had no room for a walkway around it, this it is pierced by an archway on it's north and south sides, allowing space for processional routes. Today these arches are glazed in, and the main points of entry are via the Georgian south porch or the modern parish rooms extension abutting the north west corner.

Upon entering the church one is immediately aware of the contrasting levels of light, the nave being a fairly gloomy space whilst beyond it the chancel glows like a beacon, beckoning us towards it. The nave aisles are surprisingly spacious, almost of equal volume to the nave itself; that on the north side has more recently been converted into a separate parish room, subdivided from the rest of the church by glazed screens filling the north arcade.

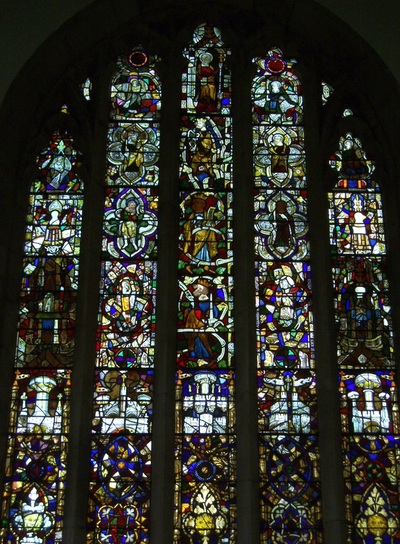

The focal point of the interior is the large east window, the real treasure of this church, being filled with a college of fragmentary medieval glass. This luminous patchwork lures us eastwards, into the light-bathed chancel, for a closer look at this archaeological jigsaw puzzle.

The focal point of the interior is the large east window, the real treasure of this church, being filled with a college of fragmentary medieval glass. This luminous patchwork lures us eastwards, into the light-bathed chancel, for a closer look at this archaeological jigsaw puzzle.

Stained Glass

The church has mostly plain glazed windows with stained glass confined to the east windows of the chancel and south aisle (along with a couple of fragments elsewhere). The latter is the only Victorian window in the church, with three lights on an Easter theme by John Hardman Studios of Birmingham.

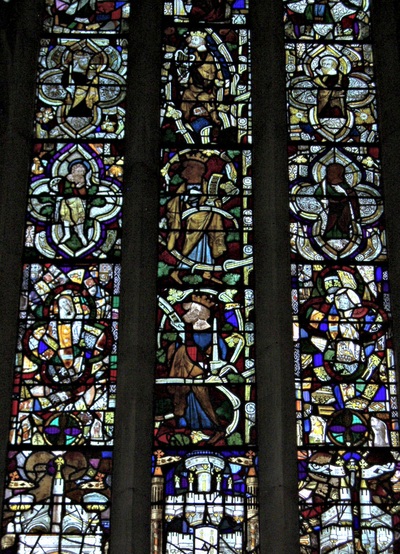

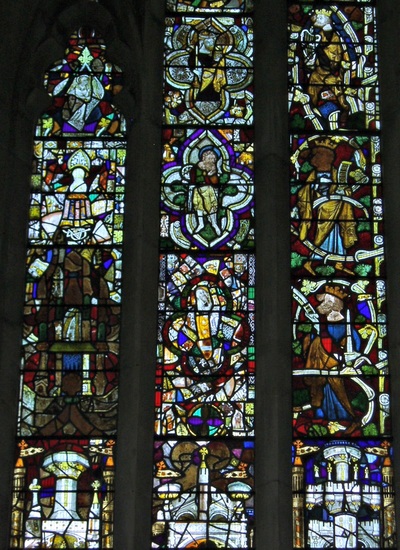

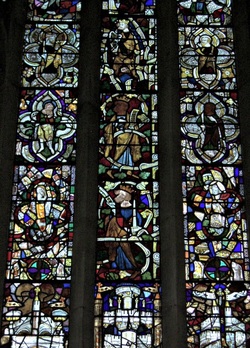

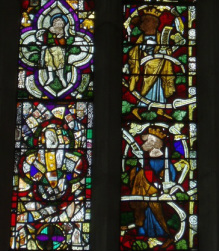

The east window is of the greatest importance here; its tracery is a Victorian restoration, based on surviving medieval work elsewhere in the church, but the glass is mostly 14th & 15th century, collected here in it's present form in the mid 19th century(augmented by some Victorian material in the lowest register of panels). The most prominent panels are the three 14th century figures of kings (David can be recognised with his harp) in the central light, which clearly belonged to the more extensive Jesse Tree sequence in the east window at nearby Merevale church, and are therefore likewise believed to originate from Merevale Abbey Church (little else of which survived the Dissolution).

Most of the remaining glass is likely to be original to the church, including the St Margaret at the centre top, and the four figures of male saints in quatrefoils (later 14th century) which are clearly recognisable as former tracery lights, and a perfect match for the openings in the head of the east window of the north aisle here (isolated pieces of glass of the same date survive in the tracery of one of the aisle's side windows).

The 15th century elements in the east window mostly consist of a row of canopies, but these suggest there must have once been some impressive figures standing beneath them. This is borne out by a fine bearded head in one of the north chancel windows, of high quality and possibly even from John Thornton's workshop in Coventry. It could well be that these fragments represent the pre-Reformation east window here, as all the other windows retain their 14th century stonework, and that of the east window has been restored to a more compatible design by the Victorian restorers, so perhaps it had been reworked in late medieval times? We will never know for sure..

The east window is of the greatest importance here; its tracery is a Victorian restoration, based on surviving medieval work elsewhere in the church, but the glass is mostly 14th & 15th century, collected here in it's present form in the mid 19th century(augmented by some Victorian material in the lowest register of panels). The most prominent panels are the three 14th century figures of kings (David can be recognised with his harp) in the central light, which clearly belonged to the more extensive Jesse Tree sequence in the east window at nearby Merevale church, and are therefore likewise believed to originate from Merevale Abbey Church (little else of which survived the Dissolution).

Most of the remaining glass is likely to be original to the church, including the St Margaret at the centre top, and the four figures of male saints in quatrefoils (later 14th century) which are clearly recognisable as former tracery lights, and a perfect match for the openings in the head of the east window of the north aisle here (isolated pieces of glass of the same date survive in the tracery of one of the aisle's side windows).

The 15th century elements in the east window mostly consist of a row of canopies, but these suggest there must have once been some impressive figures standing beneath them. This is borne out by a fine bearded head in one of the north chancel windows, of high quality and possibly even from John Thornton's workshop in Coventry. It could well be that these fragments represent the pre-Reformation east window here, as all the other windows retain their 14th century stonework, and that of the east window has been restored to a more compatible design by the Victorian restorers, so perhaps it had been reworked in late medieval times? We will never know for sure..

Monuments & Furnishings

|

Few furnishings have survived of great antiquity apart from the striking 15th century font, a large and somewhat bulky piece at the west end of the south aisle. It has suffered some damage, having been removed from the church, presumably sometime in the Georgian period, and forgotten until 1910 when it was identified in the Vicarage garden and promptly restored to its proper place. Only the bowl itself is old, and its upper surfaces seem to have been cut down for some reason.

|

Most of the rest is Victorian or later, aside from the most unusual (and amusing!) Royal Arms I've ever seen in a church; this gilded wooden group (c1700) carved in high relief simply consists of the heads of the Lion & Unicorn supporters with a crown between them. Whether this represents fragments of an otherwise lost more standard group or an 'economy version' of the usual type is hard to tell, but I'm inclined to believe the latter. The effect is somewhat cartoonish and the lion's 'laughing' expression is not quickly forgotten!

At the west end of the nave flanking the organ are two large wooden tablets dating from 1833 commemorating the Martyrs of Mancetter, Robert Glover & Joyce Lewis, who were put to death during Queen Mary's reign (in 1553 & 1557 respectively). The finest monument here is on the north side of the chancel, the impressive Baroque tablet in marble with a bust of Edward Hinton (d.1690), shown in armour and periwig. Large but less ambitious marble tablets of a later date can be found in the north aisle, commemorating members of the Bracebridge family.

St Peter's will reward a visit but sadly the church is normally kept locked without keyholder information (like most in this northern part of the county) so unless one gets lucky (before/after a service or function) an appointment will likely be necessary to see inside the church.

Aidan McRae Thomson 2014

Aidan McRae Thomson 2014